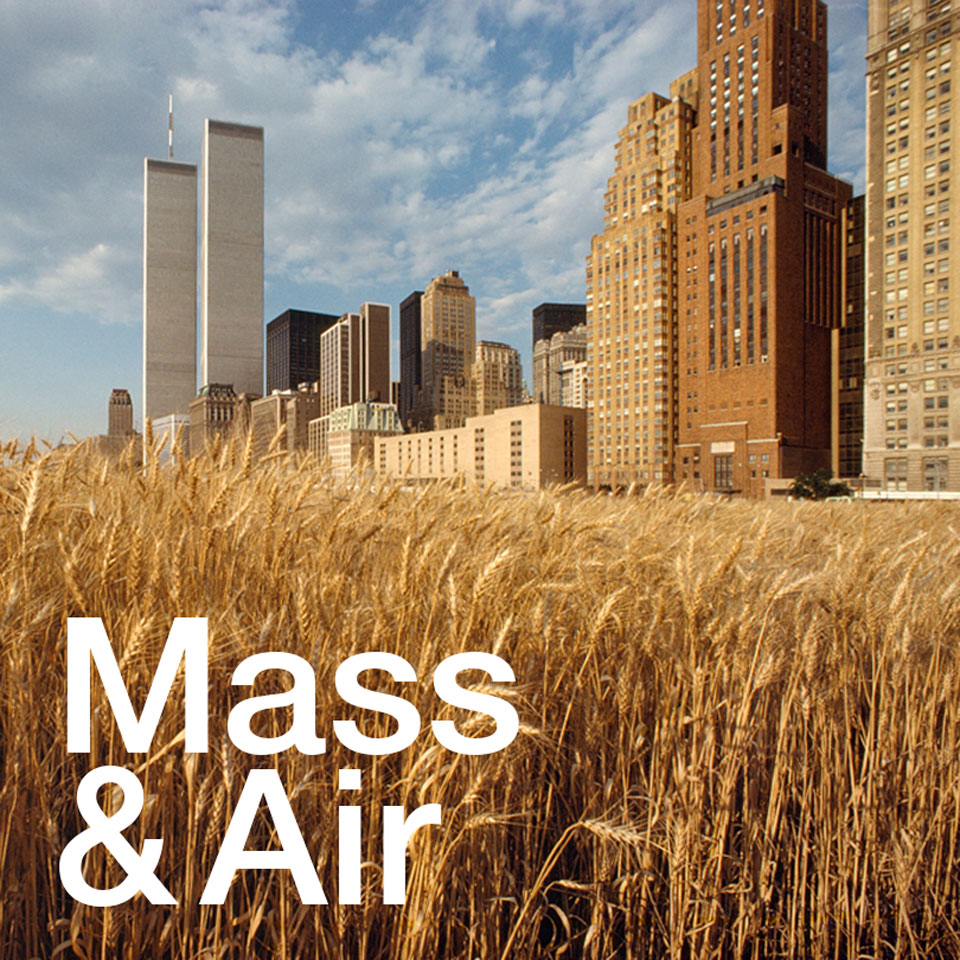

Mass & Air

We were asked by the Architecture Foundation to write about a current concern of our practice, what started as a studio conversation has grown to become a manifesto for our practice alongside our teaching studio:

How do we keep on doing what we’re doing whilst fundamentally changing how we get there? That’s the current concern of our practice.

We believe in an architecture of continuity; moving forwards whilst working with the diverse, established characters and qualities of the places we find. To some degree this has relied upon the adoption of familiar materials and conventional ways of making buildings (of course, we do then hope to subvert the ordinary to transform it to something extra-ordinary but we’ll save that story for another day).

In light of the responsibility our profession and industry has to participate in a necessary and urgent response to the climate emergency, is such practice still possible? So many of those materials we understand to have serious consequences in terms of the carbon generated during their production (especially when combined with the petro-chemically derived layers of contemporary construction). This isn’t to say they are off limits, more that their use must be within limits.

We seek to ‘hold’ the architectural language, which is an expression of the values we have in relation to the cities that people enjoy. How do we achieve buildings with a mass and presence, a dignity and civic responsibility, within this alternative framework of evaluation? (It’s civic as an attitude not ‘civic buildings’)

It leads us to radically reconsider what it means for a practice such as ours? How do we keep on making buildings that feel familiar and have a sense of permanence and weight (visual weight if not physical weight); buildings that we feel are ‘correct’ for the places they are situated within. Buildings that communities are comfortable with.

The management of this pivotal moment is in the hands of our profession. The immense shift in values, supported by advances in building technology associated with the generation and then proliferation of Modernism, led to a remaking of cities that we now acknowledge the majority of society were not comfortable with. This is not that moment again, that previous race to modernise led to a disastrous breakdown in trust of our profession that we are still having to repair. We need to be fast, thoughtful and radical, but also careful.

We don’t think the generic application of wood as seen in rendered images of future proposals across multiple countries is the sole approach in the UK, we don’t yet have a well-managed, sustainable and established timber supply chain. (But let’s get on with putting that in place for future generations.) So, out of necessity, without reliable alternative supply chains in place, this change will be incremental and the solutions, hybrid.

We also believe that if we continue to build in an architectural language that is comfortable and familiar, the adoption of such solutions by communities and statutory authorities will be faster and the impacts greater. (We’re still being asked to adjust proposals to use bricks in virtually every planning meeting we go to…)

What are the hybrid methods of construction that will allow us to make buildings specific to place? We don’t yet know, but need to, and fast. There is remarkable potential.

We must do all that we can in the UK, taking the view that we are a small country and our potential global impact will be minor is not acceptable. We need to test models in the UK that have the potential to be adapted and adopted by other cultures and communities, at least in those areas of the world that have similar climate and material resource. Outside of the construction sector the UK frequently looks enviably at smaller countries to be inspired by alternative models. Let us try and deliver that global role for our industry.

It is no doubt a challenging time to be an architect, but there is the tangible sense that the potentials of this re-evaluation, being crucial to the conversation, is inspiring us all.

We’re seeking mass that’s as light as air.

Image: Agnes Denes, Wheatfield – A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Lower Manhattan; 1982

We were asked by the Architecture Foundation to write about a current concern of our practice, what started as a studio conversation has grown to become a manifesto for our practice alongside our teaching studio:

How do we keep on doing what we’re doing whilst fundamentally changing how we get there? That’s the current concern of our practice.

We believe in an architecture of continuity; moving forwards whilst working with the diverse, established characters and qualities of the places we find. To some degree this has relied upon the adoption of familiar materials and conventional ways of making buildings (of course, we do then hope to subvert the ordinary to transform it to something extra-ordinary but we’ll save that story for another day).

In light of the responsibility our profession and industry has to participate in a necessary and urgent response to the climate emergency, is such practice still possible? So many of those materials we understand to have serious consequences in terms of the carbon generated during their production (especially when combined with the petro-chemically derived layers of contemporary construction). This isn’t to say they are off limits, more that their use must be within limits.

We seek to ‘hold’ the architectural language, which is an expression of the values we have in relation to the cities that people enjoy. How do we achieve buildings with a mass and presence, a dignity and civic responsibility, within this alternative framework of evaluation? (It’s civic as an attitude not ‘civic buildings’)

It leads us to radically reconsider what it means for a practice such as ours? How do we keep on making buildings that feel familiar and have a sense of permanence and weight (visual weight if not physical weight); buildings that we feel are ‘correct’ for the places they are situated within. Buildings that communities are comfortable with.

The management of this pivotal moment is in the hands of our profession. The immense shift in values, supported by advances in building technology associated with the generation and then proliferation of Modernism, led to a remaking of cities that we now acknowledge the majority of society were not comfortable with. This is not that moment again, that previous race to modernise led to a disastrous breakdown in trust of our profession that we are still having to repair. We need to be fast, thoughtful and radical, but also careful.

We don’t think the generic application of wood as seen in rendered images of future proposals across multiple countries is the sole approach in the UK, we don’t yet have a well-managed, sustainable and established timber supply chain. (But let’s get on with putting that in place for future generations.) So, out of necessity, without reliable alternative supply chains in place, this change will be incremental and the solutions, hybrid.

We also believe that if we continue to build in an architectural language that is comfortable and familiar, the adoption of such solutions by communities and statutory authorities will be faster and the impacts greater. (We’re still being asked to adjust proposals to use bricks in virtually every planning meeting we go to…)

What are the hybrid methods of construction that will allow us to make buildings specific to place? We don’t yet know, but need to, and fast. There is remarkable potential.

We must do all that we can in the UK, taking the view that we are a small country and our potential global impact will be minor is not acceptable. We need to test models in the UK that have the potential to be adapted and adopted by other cultures and communities, at least in those areas of the world that have similar climate and material resource. Outside of the construction sector the UK frequently looks enviably at smaller countries to be inspired by alternative models. Let us try and deliver that global role for our industry.

It is no doubt a challenging time to be an architect, but there is the tangible sense that the potentials of this re-evaluation, being crucial to the conversation, is inspiring us all.

We’re seeking mass that’s as light as air.

Image: Agnes Denes, Wheatfield – A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Lower Manhattan; 1982